St Stephen's Parish

Serving the Catholics of Skipton, Craven and the Dales

Part Two: How the Recusants survived in Skipton

16th century England was certainly a volatile place to live in. The Catholic-Protestant divide worsened with with the polemics, violence and contrasting reigns of the Protestant king Edward VI and the vengeful Catholic queen Mary Tudor, who presided over 273 Protestant burnings. Eventually, Queen Elizabeth I came to the throne, determined to set a more moderate course. Nevertheless, she fell under the influence of her Protestant Court and in 1559 she passed the Act of Uniformity which introduced heavy fines on Catholics who did not attend the established church services. Consequently, recusant Catholicism became a largely aristocratic enterprise. Pope St Pius V further aggravated matters by excommunicating the queen in 1570 and she responded by persecuting the Catholics more vigorously and restricting their movement. Recusants were now regarded as traitors in their own land.

Meanwhile, Catholic Europe was finally moved to reform. An Ecumenical Council was called at Trent in 1545 and it strove to address laxity and abuse in the Church at all levels. As a result, there arose many great saints who furthered the reform of the Church, seminaries to train priests and in the rise of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) who were founded by St Ignatius Loyola. England was now seen as a mission land and priests from Douai College and Rome were sent to England to minister to Catholics. However after 1559, for an Englishman to be ordained a priest was ipso facto treason. At the forefront of this missionary activity were the Jesuits who were to become the first pastors of St Stephen's Church in the 19th century.

|

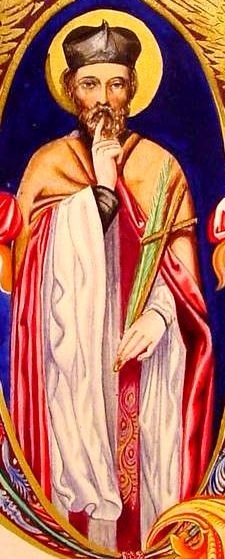

Right: an illustration showing a martyr-priest from Douai College. This illustration is taken from one of the Term Books kept in the Ushaw College archives. From 1577 quite a few of these young priests in their early twenties were martyred by the State. St Cuthbert Mayne was to be the first of over 300 men who were killed for ministering to English recusant Catholics. Many died within months or days, some even hours, of landing at Dover. From 1585 it was treason to harbour priests and St Margaret Clitherow, a butcher's wife from York and patroness of our church in Threshfield was crushed by rocks for extending hospitality to priests. From 1583 - 1603, some ninety six seminary-trained priests of Yorkshire birth arrived on the English mission. The centre of Catholicism lay on the Lancashire border, around Stonyhurst and there were over forty gentry Catholic families. The priests served from their homes and said secret Masses for the families, household and their tenants. Ingenious ways were adopted to announce Mass. For example, at Myddleton Lodge in Ilkley, washing was hung on the line. Confessions were often heard under a hedge or in various houses and there could be as many as six hundred penitents. If the houses were raided, the priests were hidden away in secret hiding holes such as the one at Ripley Castle. Henry Tempest (1537 - 1605) of Broughton seems to have emerged as a recusant only in his last years and the Tempests were to become instrumental in the building of St Stephen's. The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 saw a new wave of persecution but the 17th century was not quite as severe as Elizabeth's reign although martyrdom continued, anti-Catholicism demonstrations flared up and new penal legislation was passed to further restrict the rights of recusant families. The House of Orange was given the Crown of England by Parliament in 1688 so that England might remain Protestant as James II had converted to Catholicism. Consequently in 1692, new laws were enacted to prevent Catholics from inheriting property or buying or selling land, land tax on Catholic properties was doubled and Catholics were deprived from entering any profession or studying at Oxford and Cambridge. In 1701 the Throne was forbidden to a Catholic, a law which still stands in the 21st century. In the 17th century, Broughton had the services of Benedictine, Jesuit and secular priests and there seems to have been a regular and frequent supply after 1648. In January 1694, Fr Thomas Burnett SJ came to Broughton and resided there until his death in 1727. Thereafter, Broughton remained a Jesuit residence. |

|

The 18th century was a time of greater toleration for Catholics and the Relief Acts of 1778 and 1791 allowed Catholics property rights and their own schools, which Catholics still benefit from. St Stephen's Church has a primary school and had a girls boarding school run by a women's religious order. The French Revolution in 1792 brought an influx of 8000 priests and nuns into England. Included in this wave was the ancient seminary at Douai which eventually set up home in Ushaw near Durham and in Ware. Of the two, Ushaw College still remains as the North's house for priestly formation and descendent of the world's oldest seminary. Finally in 1829 the Catholic Emancipation Act was passed. This saw a great surge of Catholic activity as churches and schools were built, largely on the pennies of poor but faith-filled Irish immigrants. However, it was still forbidden for clergy to wear clerical garb in public, for Catholic churches to have spires or bells - St Stephen's only had a bell installed in 1884 - and for Catholic dioceses to adopt established Church of England titles, hence Westminster diocese in London.

Nevertheless, in this period of extension and mission, St Stephen's Church was finally built and established as a parish. Read on!

Broughton Hall, near Skipton, from the air.

Click here for Part Three of the History of the Parish